After the Battle of First Manassas in July 1861, the North and the South realized that this might not be the quick easy war each had predicted. The two armies settled in Northern Virginia with the Potomac River as their demarcation line.

At Leesburg, Virginia, some thirty-five miles up the Potomac from Washington, was a small Confederate force. Northern leaders believed that a minor demonstration was needed to push the Confederates back from the river and secure a large part of Northern Virginia for the Union.

Across the Potomac from Leesburg, three Union infantry brigades under Brig. Gen. Charles Stone, which he somewhat pretentiously named “The Corps of Observation,” watched the Confederates.

In 19th Century battles, terrain had as much to do with military success or failure as anything else. At the edge of the Potomac River near Leesburg was a “bluff” or steep cliff, between eighty and a hundred feet high, leading down to the water. At the top was an eight-acre open field, with only single-file dirt pathways down to the river. In the middle of the river was 500-acre Harrison’s Island, extending for three miles, impeding direct access from the Maryland shore to the Virginia shore.

On the night of October 20, 1861, twenty scouts from the 15th Massachusetts crossed the Potomac to determine Confederate positions near the bluff named for the Ball family. Because of the sheer ruggedness of Ball’s Bluff, it was thought to be unguarded by the Confederates.

The scouts’ advance across the river involved not one, but two amphibious landings. It was complicated, and the scouting party took several hours to reached Ball’s Bluff. Once atop the cliffs, they moved to within two miles of Leesburg. Ahead, in the dim moonlight, they saw what they thought were about thirty tents of an encampment. Receiving the intelligence, Stone ordered Col. Charles Devens and his 300 troops to cross the river and destroy the Confederate camp.

Even though they started for the Virginia shore at midnight, it was about 4:30 a.m. when they all shuttled to below the Bluff. When they arrived at the spot where the tents were reported, it turned out to be a line of trees on the ridge.

Col. Edward Baker—Lincoln’s good friend “Ned”—was in command of the entire force across the river in Virginia. Lincoln and Baker’s friendship went back to 1835, when Baker moved to Springfield, Illinois, to practice law. They renewed their friendship when Baker was serving in the Senate, while Lincoln was President.

When the Civil War broke out, at fifty years old, Baker volunteered. In time he commanded the 71st Pennsylvania Regiment from Philadelphia.

On the morning of October 21, 1861, Baker found himself in command of a large reconnaissance force moving into rebel territory at Ball’s Bluff.

Before Baker even arrived on the Virginia Side of the Potomac, fighting had suddenly flared in the field at the top of Ball’s Bluff. A panicked courier ran into Col. Baker on the towpath of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal and shared his concern of potential military catastrophe on the bluff above the Potomac. Baker responded by galloping off toward the battle saying he was taking his entire force across.

More Confederates arrived upon the small battlefield, pressing the Union troops toward the Potomac. Baker, who was supposed to be in command, was still on Harrison’s Island. Chaos and confusion began to creep into the Union battle plan.

Now the battle seemed to take on a life of its own. Confederates called in reserve troops while Federal forces were still crossing the river. By 12:30 p.m., Confederates had beaten up the Union force, which withdrew closer to the Bluff. There was a lull in the fighting as even more troops from both sides arrived on the field and fell into formation. Still, Col. Baker was still nowhere to be seen.

But the Confederates were also having organizational problems. At least one regiment was running out of ammunition. Others were close.

By 2:15 p.m., Baker finally made it to the battlefield and, without personal reconnaissance, began to orchestrate his troops into strange formations, some of them into an “L” shape line. But the real problem was that his formation had no depth; there was no room with the Bluff only 15 feet behind them. Baker seemed happy with the disposition of his troops, even taking time to quote poetry. Only one officer suggested that the line was vulnerable at a certain point. He was ignored by Baker. Firing broke out and the folly of Baker’s tactical arrangements would soon become reality.

The Confederate line eventually formed a semi-circle around the Federals, naturally flanking them. With their back to the Bluff, Union commanders were hampered by the lack of space in which to maneuver. As the rebels pressed them, some of the officers realized their predicament: there was nowhere to go except over the cliff to their rear, then where? It took hours to shuttle the men across from Harrison’s Island on the seven boats that could be found. In an emergency, a full-scale retreat, how could they get back?

Around 4:30 p.m., Col. Baker was walking in front of his lines, observing the battle, when a body of Confederates rushed out of the woods to his front. According to eyewitnesses, a large redheaded Confederate emptied his revolver into Baker, killing him instantly. There was a heated battle between the two sides over Baker’s lifeless body, which the Federals won. The redhead was killed in the fight and Baker’s body was carried from the field, down a cow path along Ball’s Bluff, and into a flatboat filled with wounded being evacuated. Now things for the Federals began falling apart fast.

On the battlefield, no one knew who was now in command. Strategy as to extricating the men from this battle differed. One officer wanted them to fight their way through the Confederate lines to safety. Their charge was broken up by Confederate fire. Weird stories began to circulate that the charge was led by a Confederate as a ruse to bring the Federals into a trap; since no one was able to identify the officer, others believed a bizarre rumor that it was a phantom from the spirit world leading the invading Yankees to their doom. Later, a Federal officer admitted he led the charge, but good ghost stories die hard: the battlefield is allegedly still haunted by the phantom officer, as well as the disgruntled spirits of those sacrificed there.

The sun was setting and the battlefield of Ball’s Bluff was indeed beginning to take on an eerie demeanor, which is why when one officer ordered his men to withdraw to the “ferry,” the order was quickly passed along and repeated. With the river so close, albeit a hundred feet down, it didn’t take long for the retreat to turn into a rout.

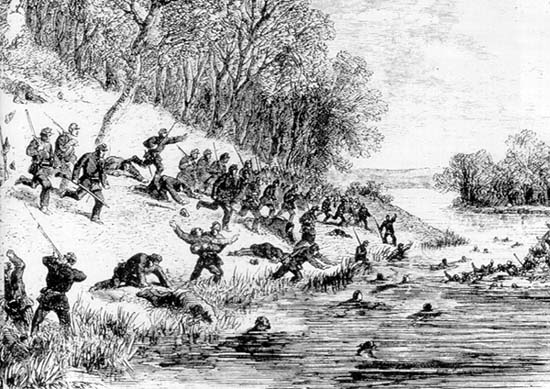

Men ignored evacuating single-file down the cow path and began rushing headlong down the bluff. Some stumbled and fell, cart-wheeling down the slope. Others leapt into the growing darkness and landed upon their comrades, breaking limbs and crushing skulls on the jagged rocks below. Once they got to the riverbank, there was no place to go. The few boats they had overflowed with the wounded. As the boats left the bank, men waded into the water and tried to climb in, capsizing the already overloaded vessels and sending the helpless wounded into the swift current to drown. Some decided they could swim the fifty feet to Harrison’s Island. They took off their coats, but their wool pants and jackets soon absorbed enough of the Potomac River water to drag them down.

Confederates were now at the top of the bluff and began firing down at the Federal masses huddled on the shore—easy targets. As well, they plinked away at the hundreds of heads bobbing in the river.

The few small boats were ferried back and forth across the river numerous times through the growing darkness, but many of the Union soldiers left on the Virginia side for too long were captured and sent to Confederate prisons. Other than rounding up prisoners, the Confederates apparently had had enough fighting for one day. They retreated back to Leesburg leaving a handful of pickets to watch the river.

Word of Baker’s death reached Lincoln and the message hit him like a blow. He staggered unsteadily for a moment, his large hands clutching his chest.

The Battle of Ball’s Bluff involved about 3,300 men, evenly split between sides. Casualties as reported in the Official Records were a little higher on the Union side, with 49 killed to 36 killed for the Confederates, and 158 wounded to 117 wounded for the Confederates. Other sources place the Union dead at 119 and higher. The real discrepancy comes in the figures for the missing. According to the Official Records, the Confederates had only 2 men missing; the Union reported 714 missing, many of which were captured.

The battle was over, but the horror was about to begin.

Within two weeks, bodies began to arrive in Washington via the muddy waters of the Potomac. Five bodies were pulled from the water near the Chain Bridge, mutilated by their journey; others were caught in the rocks near Great Falls; another at the wharf at 6th Street. At Long Bridge, Georgetown, and as far as opposite Fort Washington, bodies, some without wounds, obviously drowned, continued to appear.

When the full extent of the debacle was evident (although the casualties would soon seem miniscule next to later battles) fingers began to be pointed. The most obvious person to blame was Col. Edward Baker, due to his tactical arrangements (which would have included plans for withdrawal, if needed) on the battlefield. But this did not sit well with his fellow Congressmen, many of whom thought their volunteer army should be commanded by volunteers, (perhaps Congressmen) not West Pointers.

A brand new committee, the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, was formed to get to the bottom of the Ball’s Bluff catastrophe. According to one historian it became “the most influential, meddlesome, mischievous and baneful committee in the legislative history of the United States.”

Today, one of the smallest National Cemeteries in the nation sits atop Ball’s Bluff and holds the mostly unidentified dead from the ill-conceived battle.

The battle was over, but tales of the unquiet dead were about to begin.

Less than a year after the battle, a Maine soldier, in the area of Harrison’s Island, wrote in his diary that comrades on picket duty reported hearing unsettling noises from the woods and river shore: “unearthly” he called them. Boatmen on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, which ran alongside the Potomac on the Maryland shore, began calling this section of the canal “Haunted House Bend.” They reported screams and moans emanating from the area. Mules towing the barges became spooked; perhaps they saw the red-bearded man and African-American woman appear…then disappear, as reported by those who traveled this section of the C & O Canal. (“Ranger Geoff” https://www.canaltrust.org/discoveryarea/edwards-ferry-and-haunted-house-bend/, accessed, 9/22/2020, 4:18 pm.)

Reports from the 1860s record the ghostly plodding of hooves from unseen horses and the unmistakable rattle of cavalry sabers. Perhaps they were just the pre-cursor to the phantom Union cavalry that manifested itself, to the horror of early visitors to the battlefield.

At least some of the sightings are attributed to Abraham Lincoln’s friend Col. Edward Baker. He not only botched the battle, but may have brought something onto himself when he bragged on the eve of the battle, “On the morrow I’ll be in Leesburg, or hell.”

Other stories that have come from the area: people walking their dogs notice the canines will whimper and try to avoid certain parts of the area; strange animated mists will appear before visitors, grow to the height of a man, then quickly dissipate; a soldier, running across the road in a crouch has caused accidents; cold spots are felt, as well as feelings of being watched; phantom footsteps and voices are heard coming from the woods.

L. B. Taylor, Jr., the “dean of Virginia ghost stories,” recounts many tales in his book, Civil War Ghosts of Virginia. In the early 1950s, some thrill-seeking teenagers drove out to the Bluff, but were forced to quickly retreat at the sounds of “terrible screams” from a source no one could pin-point. They ran back to their car, started it, put it in gear…but it wouldn’t move, as if something unseen and otherworldly were holding it hostage. The event lasted for several minutes. Then, as if suddenly released, the car lurched forward and they were able to speed off. Once home, they inspected the car. To their horror they found two huge muddy handprints from gloved hands in recently dried clay on each side of the rear of the car. Evidence, perhaps, of something more sinister than ghostly soldiers residing at the Bluff?